Share this

Storytelling + Inbound Marketing, the Likely Pairing That's Just Now Catching On, a Conversation With Gabriela Pereira

by Greg Lukach on Tue, Oct 15, 2019 @ 09:30

Marketers are finally talking about storytelling. A lot, in fact.

The frequency of "Why Use Storytelling in Marketing?" blog posts and articles has gone from occasional to ubiquitous over just the past few years.

It's no coincidence that I attended three sessions at INBOUND 2019 alone about how storytelling can be used to improve marketing messages and strategies.

In my last blog post—which, to be fair, was yet another version of the "Why Storytelling?" post—I mentioned that one of those INBOUND 2019 speakers was Gabriela Pereira. She's the founder of DIY MFA, an organization that identifies itself as the "do-it-yourself alternative to a master's degree in writing."

Gabriela stood out at INBOUND. It wasn't just her upbeat and quirky demeanor (she arrived on stage and gleefully belted out, "Hello, word nerds!"—"Word nerds," she explained, is what she calls those within the DIY MFA community).

Rather, it's that Gabriela isn't just an author and a marketer. She's someone who's looking to understand her craft at a scientific level. She digs into the research and examines why humans are hardwired to demand storytelling.

I had the opportunity to speak with Gabriela after INBOUND and talk about why storytelling and inbound marketing make a perfect pair—that people are finally talking about.

The interview below has been edited slightly for clarity.

Greg Lukach: My first question is really just me wanting to validate an observation of mine. But why is there such a focus on the power of story in inbound marketing messaging right now? It's no coincidence that I attended three sessions about storytelling alone at INBOUND and it seems like there's this intense focus on it at this moment. Do you have any insight into why?

Gabriela Pereira: As someone who is a storyteller first and a marketer second, my question would actually be why not sooner than now? Why has it taken people this long to pay attention to the power of storytelling?

I think part of it is Don Miller's StoryBrand Framework. That whole methodology has put a focus on storytelling in marketing. I also think a lot of the research that's happening in psychology and neuroscience, in particular, is moving even more in the direction of storytelling—you're seeing more people research the impact that story has on how our brains function and how story creates more empathy. Some of this research is helping determine what your brain is actually doing when you're experiencing a story.

So I think these are some of the cues we're getting environmentally that are shining a spotlight on the subject. But, honestly, there's part of me that's baffled about why it's taken this long.

Greg Lukach: Thank you for the validation! At your session at INBOUND, you talked about how each brand has a storytelling superpower that needs to be established. You said that brands should either be relatable or aspirational and they need to make a promise. The promise is that they'll either help customers change or preserve where they're at. Can you explain that?

Gabriela Pereira: Sure. Basically, this whole concept originated from me working with writers, trying to figure out how writers go about choosing the types of stories they're best able to write—the stories they won't give up on. This is where it came from. It had nothing to do with marketing.

And then, as I started working with this concept and reading a whole heck of a lot of research on the psychology of storytelling and marketing, I started to see a lot of parallels in the types of heroes we have in books and the types of brands that are out in the marketplace. As soon as I started to notice those parallels, I couldn't unsee them! Now I start to see the storytelling parallel in everything.

So, essentially, the way it works is you have two types of heroes. You have the relatable heroes—the usual people who are stuck in some extraordinary circumstance, like Dorothy who gets sent off to Oz or Harry Potter at the beginning of the series. These are regular people we can relate to because we see some piece of ourselves in those characters.

Then you have the aspirational heroes. These are the big personalities and characters. They're the James Bonds and the Jay Gatsbys. These characters don't reflect who we are right now, but they reflect who we would like to become.

The same thing is true for brands.

Relatable brands tap into that feeling of "yeah, I know what it's like." An example of this is those Credit Karma ads where you see people who are dealing with ridiculously crazy neighbors. They use Credit Karma so that they can get a house and a mortgage so they don't have to live in that crazy place.

Aspirational brands are the ones where the brand is showing something that we want to have for ourselves, whether it's luxury or a feeling of innovation or breaking boundaries. Apple is really big on disruption and presenting itself as a larger-than-life brand.

The idea is that you have these two categories of brands that most brands fall within. Now, there's a lot of gray area. No character is at either side of this spectrum, the same way that no brand is completely at one extreme or the other. It's very rare to be all or nothing. You're going to lean in one direction over another. And the fact that the characters or brands are malleable allows you to shift your messaging. If these two types of characters were in buckets rather than within a spectrum, you'd be locked in and there'd be no room for changing the positioning of your brand messaging. What you need to know is where you gravitate as a brand so that then you can start to massage your messaging and nudge it in the direction you want it to go.

Greg Lukach: What if, hypothetically speaking, you fall in the middle of the spectrum, and your brand is waffling between being relatable and aspirational? Your messaging probably loses impact, right?

Gabriela Pereira: I once heard a phenomenal quote—I forget who said it—but it was something like, "love me or hate me, there's no money in the middle." You've got to pick a lane.

Greg Lukach: How long should a brand stay in a lane? At INBOUND you talked about how Apple flipped its positioning from relatable underdog to aspirational disruptor. Are there some general guidelines around when that transition should take place?

Gabriela Pereira: I would watch the metrics really carefully. Length of time also depends on how often you're communicating with your customers. Apple actually shifted from larger-than-life to relatable and back again over a period of many years. If you look at how long that Mac vs. PC campaign ran, it was quite some time. But those were television commercials. They take a long time to produce, they take a long time to get out there and gain traction. So I completely understand why they went with it for such a long time. It probably took awhile to get enough eyeballs on it and get a sense around whether it's having an impact on customers.

If you're making this shift in a weekly newsletter and you're communicating with your customers every single week or day, and you're creating enough touchpoints with your customers, you could probably pivot a lot more quickly.

And then the other piece of it is figuring out how nimble the organization behind the brand itself is. Is it an organization where every little messaging decision is going to take a long time? If that's the case, you're probably going to need to pick a lane and sit in it for a long time.

At DIY MFA, we're incredibly nimble because we're small and I can make decisions very quickly. So, we try new things all the time. But we watch the right metrics like crazy—that's the big piece. This is so you know whether the changes you make to your messaging are actually doing what you want them to do.

If you're going to be making rapid shifts like this, make sure you're not changing multiple variables at the same time. For example, I would determine what happens when you change subject lines in emails and see whether aspirational or relatable messages in those headlines produce better results. I would test that over a period of time and then start changing up the email's body copy, etc. If you're changing too many things at once, then you don't know what made a difference.

Greg Lukach: So, how do you begin to weave storytelling into an inbound marketing buyer's journey?

Gabriela Pereira: There are three concepts at play.

There's the character, and the character piece of the puzzle is split into two parts, the character of the brand and the character of the customer. So you need to understand what archetype your brand is so you can align your messaging with the archetype of your customer—if there's a mismatch between the two.

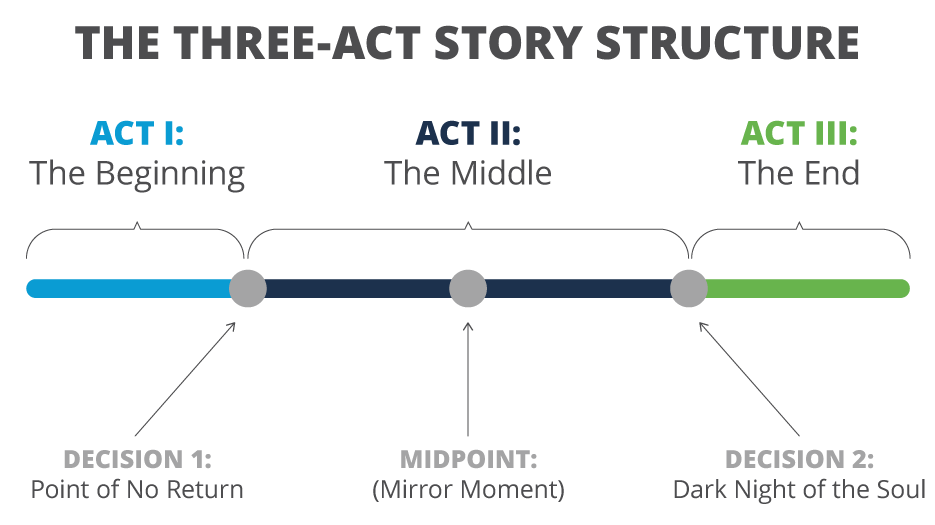

The other piece of the puzzle is the plot, which adheres to the three-act structure that most stories have. The character is going through the plot throughout the course of the buyer's journey.

As a brand, you need to understand where you're coming from, but then also where your customer's coming from. You then need to understand what three-act journey experience will ensure the only conclusion your customer will have is to open their wallet and make a purchase, or sign up for a free trial or become a fan for life—whatever the end game is for that journey.

Greg Lukach: What happens when the story's over?

Gabriela Pereira: Well, it depends on what the story was! There are so many stories or journeys a brand can craft.

There's the journey between the first touchpoint—prior to which the customer has no idea the brand exists—to finally getting customers to sign up for a newsletter or whatever tactic is capturing their name and address so that they can become part of your ecosystem.

That's one journey.

And now that this customer is in your ecosystem, they start a brand new journey, which is maybe purchasing their first product or service offering from you. And that will then be another three-act story structure. Once they make that first purchase, you now have the journey of nurturing that customer to make another purchase, etc., until they become a fan for life.

Greg Lukach: At INBOUND 2018, the big reveal was the flywheel, and a big portion of the flywheel methodology is what you're talking about. It's creating the buyer's journey—or story—that starts over again. So, after some type of customer or prospect engagement, you're upselling, cross-selling and delighting by continuing to provide them value. This is different from the traditional inbound marketing funnel where all inbound marketing objectives align with a rigid handoff to sales. Buyer's journeys are now being seen as not having an endpoint, but, rather, transitioning into another journey.

Gabriela Pereira: Yeah, or it's like a neverending system of funnels.

Greg Lukach: Yeah, true. That's curved?

Gabriela Pereira: Or like a funnel that pours into another funnel, that pours into another funnel, etc. The image I like best is actually climbing a spiral staircase because even when you come full-circle, you're not in the same place you were when you started. So it's the idea of going in a circle, but after the journey you just went on, you're elevated a bit—your customer's no longer on the same level that they were.

Greg Lukach: Right, because the next time around they can skip that baseline information gathering and dive right into more detailed educational content.

Gabriela Pereira: Exactly, and the entire messaging is going to shift. With every floor you move up, the messaging changes because your customers' needs are going to change.

Greg Lukach: We've been having an interesting conversation about storytelling's broad applications within marketing, but let's lay things out cleanly. How would you map the three-act story structure you referenced onto a typical buyer's journey? How do these two methodologies come together in the real world?

Gabriela Pereira: It's easiest to map the three-act structure onto the buyer's journey that starts with someone who is at least somewhat aware that they have a problem and ends at the point of purchase.

So, in Act I, you're introducing that the problem even exists. At this point, your customers may realize that something isn't quite right or they want something, whether that be a new car or to lose 10 pounds. Act 1 is important because it lays the ground rules for how you're going to communicate with your customers. If you think about how Act 1 functions in books and movies, it's where you learn how to read the book. You figure out whether you're going to be jumping timelines or moving from one place to another. In Star Wars - A New Hope we find out right away that we're going to be jumping around the galaxy, and that is all taught to us in that first act. We figure out very quickly how the mechanics of the story are going to work.

You then get to that decision point, that inciting incident, where the thing happens that causes a character to make a very important choice. In the Wizard of Oz, that's where Dorothy's house gets plopped down in Oz, in Star Wars, that's when Luke's aunt and uncle are killed and he decides to follow Ben Kenobi and save the galaxy. In stories, an inciting incident is usually an external event that happens that causes an internal shift in the character. The internal shift is often more subtle, but the external event and internal shift are both equally important, and you can't have just the external event and not the internal shift because, otherwise, the character would have no agency in the story. Think about The Hunger Games, and the fact that Katniss's sister's name was pulled out of the jar and then Katniss volunteers. The sister's name getting pulled is the external event—but Katniss's choice to take her place is the internal shift. The story would be completely different and have no meaning if it was Katniss's name pulled from the jar originally.

In the buyer's journey, your customer is going through the same thing. They're going to see something in the external world that is going to trigger a decision, and that decision is then going to be what instigates the rest of their journey with the brand. So getting at the heart of what that internal decision is, is really important. A lot of times brands will sell to the external problem and they're not actually tapping into what the customer's deeper desire is.

Once you get to Act II, this is where you're really nurturing that process. It's when you present that solution. You make it very clear that there is a solution and you want to get them to buy into the idea that the problem can be solved.

That leads to the moment of self-reflection in the middle of Act II, which is when the customer or prospect thinks "that could work for other people, but it's not going to work for me." You have to get your customer over that hump, where suddenly they realize, "no, that will work for me!"

You then get to the second decision prior to Act III; in literature, it's called "the dark night of the soul." This is when, in a story, the character hits rock bottom, they don't know what to do next, and that's when they find a way to pull through. In the buyer's journey, this is where a brand clearly presents why its product or service offering will solve the customer's problem and shows how it can work for them. And, if you play your cards right, up until that point you've built your customer's trust by not selling to them from Act I on. You've given them the time they need to really get to know your brand, and now you're ready to present that solution.

And, of course, Act III is easy. It's the dream come true.

Greg Lukach: So, that's primarily the post-sale or post-engagement Act? The beginning of Act III would be the sale or decision to download an offer or reach out and then the rest of Act III is where you continue to entice customers with other offerings or products.

Gabriela Pereira: I actually think of Act III as the climax, so the final showdown and the act of opening the wallet and buying the thing or engaging with the brand. It's the last battle that saves the world—it's the Death Star blowing up.

But you have to remember that there's a little piece of the story after the final showdown—the denouement in literary terms. It's the closure, the "where are they now?" moment. It's not often very long, but that little transition piece is super-important. It's where you ease your customer into another Act I, or the next level of story.

Greg Lukach: That was a really great explanation of how a traditional storytelling structure maps onto an inbound marketing buyer's journey. I feel like I have an entirely new framework to use!

Gabriela Pereira: Thank you! This is an ever-evolving concept that I've been working on for years now, so I'm always excited to see new research and continue to evolve it—if you know of any research or run across any, send it my way!

About DIY MFA: DIY MFA is the do-it-yourself alternative to a master's degree in writing. We help writers get the “knowledge without the college” so they can get their words on the page and their stories out into the world. Our approach combines the three main elements of traditional MFA programs—writing, reading and community—and adapts those elements so writers can recreate a graduate-level course of study outside the school environment.

Gabriela Pereira is the founder of DIYMFA.com, the do-it-yourself alternative to a master's degree in writing. She is also a speaker, podcast host for DIY MFA Radio and author of the book DIY MFA: Write with Focus, Read with Purpose, Build Your Community.

Share this

- Inbound Marketing (125)

- Manufacturing (82)

- Lead Generation (70)

- Website Design & Development (57)

- Social Media (46)

- Online Brand Strategy (38)

- eCommerce (33)

- B2B Marketing (26)

- Expert Knowledge (26)

- Digital Marketing (24)

- Company Culture (22)

- Content Marketing (16)

- Customer Experience (15)

- Metrics & ROI (15)

- Search Engine Optimization (15)

- Marketing and Sales Alignment (12)

- Transportation and Logistics (10)

- Content Marketing Strategy (9)

- SyncShow (9)

- Digital Sales (8)

- Email Marketing (8)

- Lead Nurturing (8)

- Digital Content Marketing (7)

- Mobile (7)

- Brand Awareness (6)

- Digital Marketing Data (4)

- Video Marketing (4)

- General (3)

- LinkedIn (3)

- Professional Services (3)

- Transportation Insights (3)

- News (2)

- PPC (2)

- SEO (2)

- SSI Delivers (2)

- Account-Based Marketing (1)

- Demand Generation (1)

- Facebook (1)

- High Performing Teams (1)

- Instagram (1)

- KPI (1)

- Marketing Automation (1)

- Networking (1)

- Paid Media (1)

- Retargeting (1)

- StoryBrand (1)

- Storytelling (1)

- Synchronized Inbound (1)

- April 2024 (1)

- March 2024 (3)

- January 2024 (2)

- December 2023 (4)

- November 2023 (3)

- October 2023 (1)

- September 2023 (4)

- August 2023 (3)

- July 2023 (2)

- June 2023 (2)

- August 2022 (2)

- July 2022 (2)

- June 2022 (1)

- March 2022 (2)

- February 2022 (1)

- January 2022 (2)

- October 2021 (1)

- June 2021 (1)

- May 2021 (1)

- March 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (1)

- October 2020 (2)

- September 2020 (1)

- August 2020 (3)

- July 2020 (3)

- June 2020 (4)

- May 2020 (2)

- April 2020 (3)

- March 2020 (9)

- February 2020 (5)

- January 2020 (6)

- December 2019 (5)

- November 2019 (7)

- October 2019 (6)

- September 2019 (8)

- August 2019 (5)

- July 2019 (5)

- June 2019 (3)

- May 2019 (2)

- April 2019 (1)

- March 2019 (2)

- February 2019 (1)

- January 2019 (2)

- November 2018 (1)

- October 2018 (1)

- September 2018 (1)

- August 2018 (1)

- May 2018 (2)

- March 2018 (1)

- November 2017 (1)

- October 2017 (1)

- September 2017 (1)

- August 2017 (2)

- July 2017 (2)

- May 2017 (1)

- April 2017 (1)

- February 2017 (1)

- January 2017 (1)

- December 2016 (1)

- November 2016 (8)

- October 2016 (7)

- September 2016 (2)

- August 2016 (2)

- July 2016 (6)

- June 2016 (3)

- May 2016 (4)

- April 2016 (6)

- March 2016 (6)

- February 2016 (7)

- January 2016 (7)

- December 2015 (6)

- November 2015 (2)

- October 2015 (3)

- September 2015 (2)

- August 2015 (4)

- July 2015 (9)

- June 2015 (9)

- May 2015 (8)

- April 2015 (8)

- March 2015 (9)

- February 2015 (7)

- January 2015 (8)

- December 2014 (7)

- November 2014 (7)

- October 2014 (5)

- September 2014 (4)

- August 2014 (4)

- July 2014 (5)

- June 2014 (4)

- May 2014 (5)

- April 2014 (4)

- March 2014 (7)

- February 2014 (9)

- January 2014 (7)

- August 2013 (2)

- July 2013 (4)

- June 2013 (6)

- May 2013 (7)

- April 2013 (7)

- March 2013 (8)

- February 2013 (5)

- January 2013 (7)

- December 2012 (4)

- November 2012 (4)

- October 2012 (2)

- September 2012 (1)

- July 2012 (1)

- April 2012 (4)

- March 2012 (5)

- February 2012 (2)

- January 2012 (3)

- November 2011 (1)

- May 2011 (3)

- April 2011 (1)

- March 2011 (1)

- February 2011 (1)

- December 2010 (2)

- November 2010 (3)

- August 2010 (1)

- July 2010 (1)

- May 2010 (2)

- April 2010 (1)

- January 2010 (1)